1km remaining, time to go all out. Sustain as much as possible, my legs screaming, and cursing someone’s idea to make that final turn/ramp so steep. 20%+ a lung buster.

Lactic Acid – A cyclist's worst enemy; “the burn”, a feeling of dwindling power and exhaustion. It builds, it builds, and before you know it, you’re beyond the point of no return.

So what is Lactic Acid?

Throughout the day, we are working aerobically and anaerobically. Aerobic exercise relies on us using oxygen around us, using our heart and lungs to activate a motion. Imagine spinning your legs on a bike without any muscular strain. This is aerobic exercise.

Anaerobic exercise occurs where breathing faster or using your cardiovascular system (ie pumping oxygenated blood around the body) won’t produce the output you need. The body turns to this anaerobic pathway for fuel. As the body breaks down glucose for energy, a by-product called lactate is generated.

These elevated lactate levels increase muscle cell acidity, causing what we know as lactic acid – that fiery burn we feel during an intense workout or exertion.

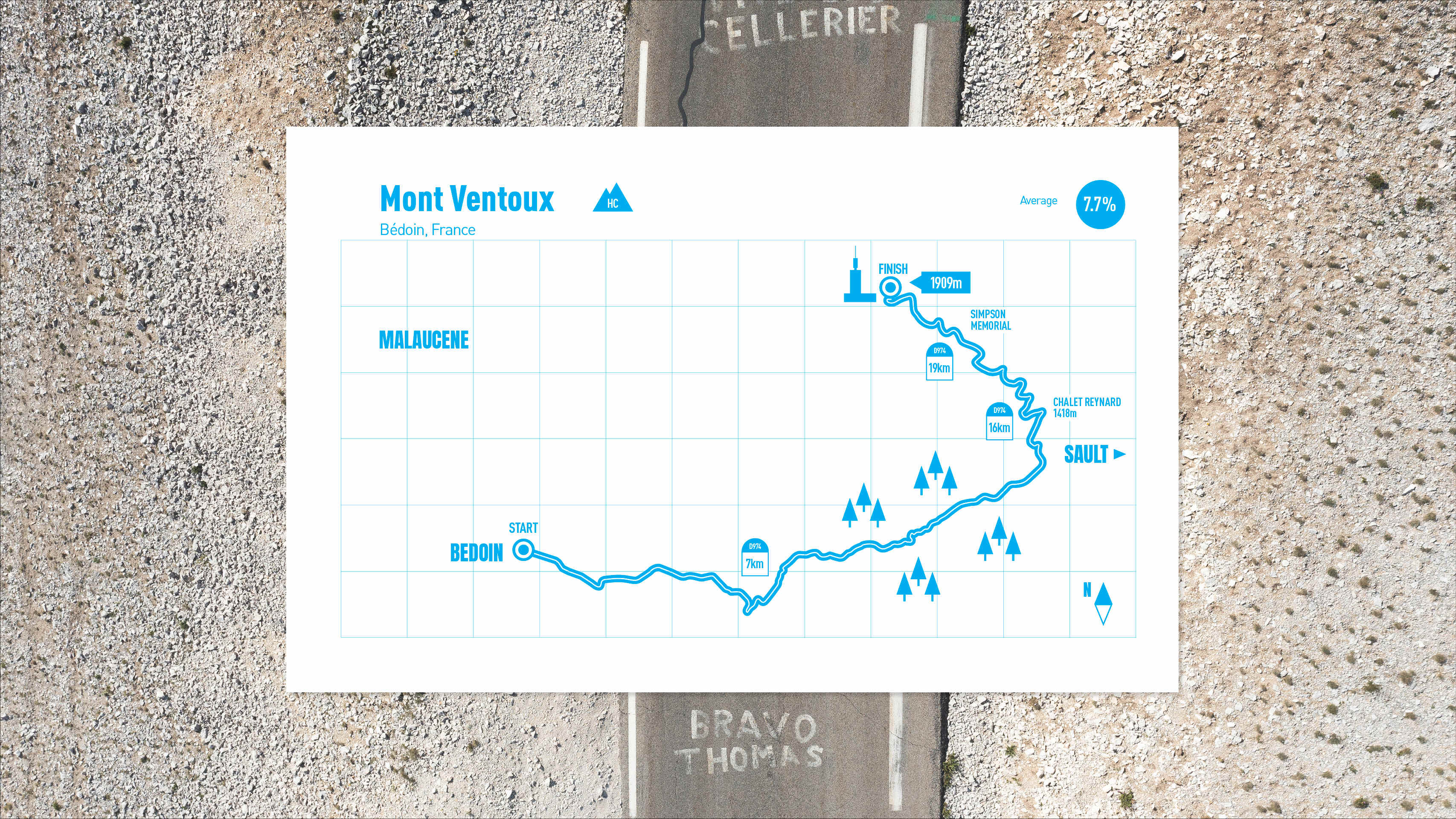

Bedoin, France. One of three pathways to Ventoux, the giant of Provence. It’s time! This climb is otherworldly. It leaps from the surrounding area, standing totally out of place. 1912m above sea level, making you wonder just how it came to be. This year the Tour de France will be submitting this beast twice. I can feel their pain whilst writing this—the first summit via the town of Sault descending to Maucelene to then climb up again from Bedoin. A casual 3056m of climb over 80km (49miles). Is it wrong to say that I’m looking forward to seeing the faces of pain as they get to the summit for the second time?

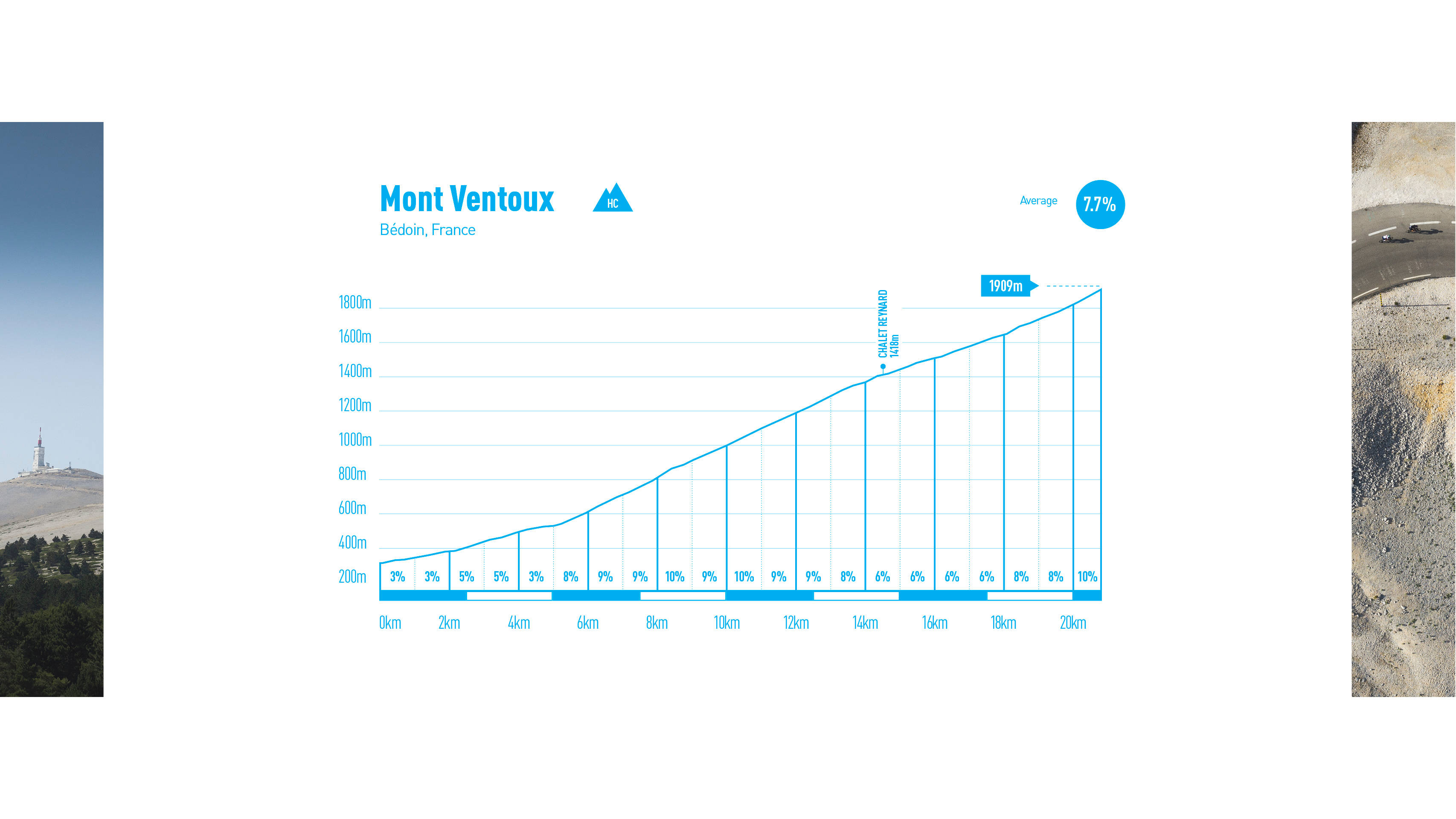

My attempt was a single attempt; it actually hadn’t occurred to me about doing the double—1579 m of climbing over 21.3km with an average of 7.3%. For myself, when the gradient goes about 7%, it has a noticeable effect on me. The ability to use my aerobic system gets diminished. At 80kgs, I am not a climber, more a rouleur. I need to ride this tactically.

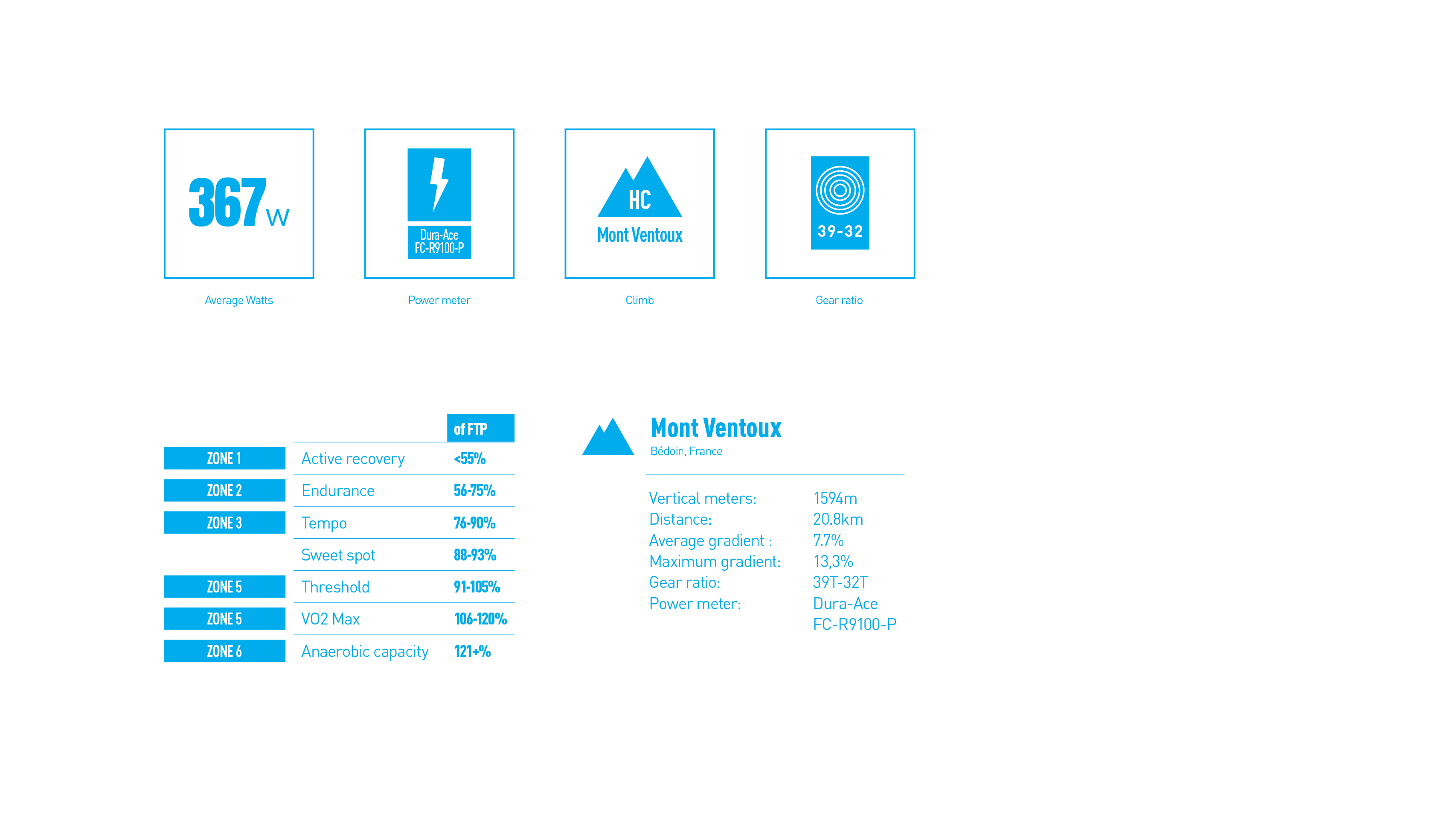

In my last article, I talked about the importance of Functional Threshold Power (FTP) as a tool to ride/pace yourself effectively during efforts. On a climb like Ventoux, which is steep and long, being able to pace yourself effectively is critical to achieving your best possible result/time. These are measured in watts of output, but it doesn’t delve into how your body is producing these watts and coping with the workload. You need a lactate threshold test (LTT) to understand this better.

My last LTT test was carried out in a sports science lab. I was on a static bike wearing an uncomfortable mask and starting at a wattage that was easy to maintain. The idea is to work out the maximum power output you can sustain for 1 hour. I start at 200w for 4 minutes, comfortably in my aerobic zone. A blood sample was collected and a board thrust in front of me asking about my perceived effort level. The wattage gets increased by 30w, and now the intervals are three minutes each, again collecting a blood sample and asking me my effort level. This continues to the point of failure. Where my legs are on fire, full of lactate acid, and I’m unable to continue. So how is this painful test useful?

It highlighted a few things for me:

- My ability to suffer is good.

- I train too hard. I produce lactate earlier than anticipated, and my body and mind have adapted to cope with these. I need to balance out my training better.

- It highlighted effective training zones

Lactate threshold Vs FTP?

Although in many ways there is an overlap and both provide useful data to train and to race, they are different. In my previous article, the FTP test provided meaningful zones and so does a lactate threshold test (LTT). However the most interesting take away from an LTT test is the wattage or workload which your body starts producing lactate acid exponentially. If you continue at that intensity or above, eventually your body will get flooded with lactate acid and you will be unable to sustain your effort, otherwise known as feeling the burn.

So taking this knowledge of where I’m going to enter into a point of no return, I clip in and go for a short warm-up ride to Maucelene before taking on Ventoux. I spend the first 10 minutes at 50% of my FTP, then doing 2 minutes on 2 minutes off and increasing the workload to 110% of FTP. 30 minutes in total before then using the remaining time back to Bedoin to spin very easily. The chill section allows me to flush out some of the lactate acid I will have created.

It starts! This route is relatively kind at the beginning, below 5% for the first 3km. It could be easy to go too hard and enjoy the speed on this section. I’m sitting 340-350w which is 140w lower than when I cease to pedal normally in my LTT (490w). I am however well into my Lactate Acid producing zone. The lactate acid clock is ticking.

Is time important? Well, yes but no. A personal best is always great - for reference Chris Froome has the KOM here in a blistering 58 minutes - but you have to ride your ride. That is why a power meter is so useful. It would be easy to see your time slipping away from you and to push harder than you should. I’m anticipating my effort to be well north of 1hr so I can’t just go at with my FTP numbers (factored at 1hr) as at some point I’d likely bonk or hit the wall. My lactate threshold test results confirmed that too.

Through some pretty hamlets and vineyards to then head into the trees. I was cocooned from the world and the views. This section feels long, and with the gradients hitting 12% at times. My riding style of spinning at a higher cadence to use more of my aerobic system (and save my body from flooding with lactic acid) is now impossible. I’ve still got a long way to go, as the road markers kindly remind me.

The view is starting to open up and I catch my first glimpse of the barren lunar rock of Ventoux. Past the junction where the Tour De France will join this route for the first summit, and this is the point where I said to myself I’d increase the watts to my FTP or above. 6km to go. If I had that board in front of me, the perceived effort would be 9/10. My legs are definitely starting to suffer.

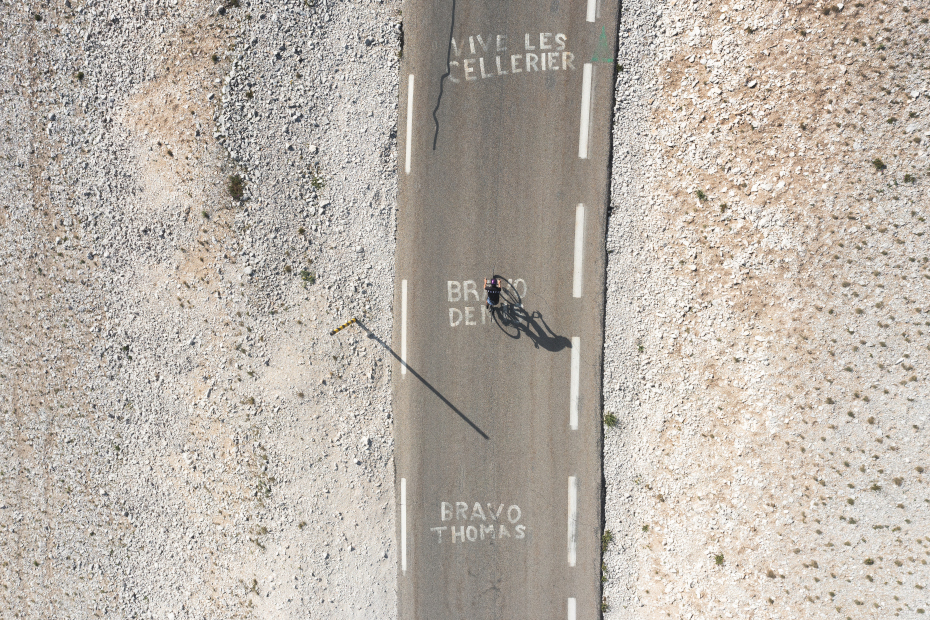

Boom! I see the infamous Ventoux tower, but not for long, as my head is down. My tactic for getting through periods of discomfort? Count to 30 slowly and focus on the wheel. 1…2…3.. and repeat. Meandering, out of the saddle for the ramps and then back down. It feels good to get out of the saddle, but it’s not as fast (for me) and it disrupts my rhythm.

The top! Time to enjoy the stunning views and to see where my efforts have taken me from.

Could I have done it twice? Yes, I think, but my approach would have had to have been entirely different. Sustaining a more moderated effort during each climb and making sure that on the descent, I use that time to flush out as much lactic acid as possible, and of course to refuel for another anaerobic effort.

As this climb told me, it’s not only the pro’s who need a power meter, but us mere mortals too. The pro’s just see bigger numbers. And with that in mind, I can’t wait to see how much bigger at this year’s Tour. Bring on stage 11!